A reflection by Aditi Deodhar on how design and material choices determine sustainability, using the everyday geometry box rounder to show how mixed materials, unnecessary packaging, and design decisions quietly create waste that ends up in rivers.

Introduction: Sustainability Is Hidden in Ordinary Objects

When we think about unsustainable products, we often imagine large, industrial waste streams.

But some of the most persistent waste comes from small, ordinary objects—used briefly, discarded quietly, and forgotten quickly.

One such object is the geometry box rounder.

A tool every child uses.

A product rarely questioned.

And yet, one that reveals how deeply design choices determine environmental outcomes.

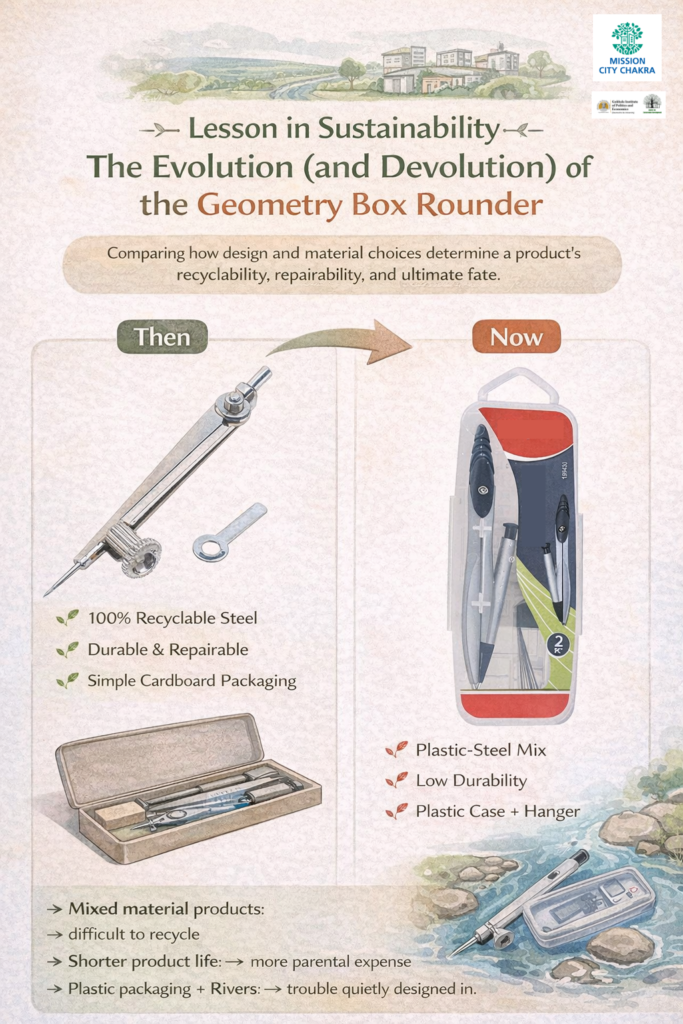

The Rounder We Once Knew

Not very long ago, the rounder was:

made entirely of steel,

durable enough to last for years,

repairable with a simple screw,

100% recyclable at the end of its life.

It came in:

a simple cardboard sleeve, or

as part of a basic metal geometry box.

It did its job—and quietly disappeared back into the pouch when not needed.

No excess.

No confusion.

No waste burden.

The Rounder We See Today

Today, many rounders have:

plastic grips bonded to steel legs,

plastic tightening knobs,

multiple material types fused together.

They often come packaged in:

thick plastic cases,

elaborate moulded shells,

hangable retail packaging with branding layers.

Once purchased, something interesting happens.

The rounder is removed.

It goes into the pencil pouch.

The plastic case is left behind.

Which raises a simple but important question:

Who was this packaging actually designed for?

Did Anyone Ask for This Change?

Let us pause and ask a few honest questions:

Were children unhappy with the old steel rounder?

Did parents demand colourful plastic cases?

Was the earlier rounder failing functionally?

Was durability a problem?

There is little evidence that users demanded this shift.

What changed instead were:

retail display priorities,

marketing differentiation,

perceived “modernisation” of products,

cost and visual branding considerations.

None of these are inherently wrong.

But none of them are neutral either.

When Design Adds Cost—but Not Value

This shift introduced:

more materials,

more components,

more manufacturing steps,

more packaging.

The result?

Higher financial cost for parents

Shorter product life

Zero repairability

Near-zero recyclability

A mixed plastic–metal rounder is:

too small for plastic recyclers,

too contaminated for metal recyclers,

too low in value for anyone to collect.

So it is discarded.

From Dustbin to Drain to River

This is where my experience with river cleanups as part of Jeevitnadi enters the story.

These rounders are not thrown into rivers deliberately.

They are:

discarded as mixed waste,

rejected by recyclers,

left unmanaged in landfills or open waste piles.

When monsoon rains arrive, waste follows gravity.

Light, mixed-material objects travel:

from streets,

to drains,

to streams,

to rivers.

Not because of carelessness—but because no system wants them.

A product no recycler values will always find its way to nature.

This Is Not a Brand Problem. It Is a Design Question.

It is important to be clear:

This is not about blaming companies.

This is not about intent.

This is not about aesthetics being “wrong”.

This is about design decisions having consequences beyond the design brief.

When materials are mixed unnecessarily,

when packaging is designed for display, not life cycle,

when durability is traded for appearance,

waste is designed in.

What Could Have Been Done Differently?

The same rounder could have been:

all-metal,

modular,

repairable,

packaged in cardboard,

sold loose or as part of a reusable geometry box.

None of this would reduce usability.

None of this would harm learning.

None of this would inconvenience children.

But it would:

reduce material extraction,

eliminate mixed-waste burden,

protect rivers,

lower long-term cost.

The Bigger Design Lesson

The rounder is not unique.

It represents thousands of products where:

durability was replaced by disposability,

simplicity by complexity,

recoverability by branding layers.

These decisions are often invisible at the point of purchase—but very visible at the point of disposal.

And once a product reaches that stage, it is too late.

Conclusion: Sustainability Is Decided Before the Product Exists

The fate of the rounder was not decided in a child’s hand.

It was decided on a design table.

End-of-life outcomes are not waste problems.

They are design outcomes.

If we want fewer products in rivers,

fewer burdens on parents,

and fewer impossible waste streams,

we must ask harder questions earlier.

Not after the product is sold.

But before it is even made.

A Closing Thought for Designers

When we simplify design,

nature breathes easier.

And sometimes, the most sustainable innovation

is simply not changing what already worked well.

Download this information in the form of a case study which can be used as a teaching material in Design Schools, a discussion starter in Design Studios.