From Consumer Responsibility to Design Responsibility

The R Framework is often framed as a consumer responsibility. In this blog, Aditi Deodhar explains why real waste prevention must begin at the design stage—before products reach consumers—and why redesign is the most powerful intervention

Introduction: Why Are Consumers Asked to Fix a Design Problem?

Every sustainability conversation eventually reaches the same advice:

-

Refuse what you don’t need

-

Reduce your consumption

-

Reuse what you have

-

Recycle responsibly

This R Framework is repeatedly communicated as a consumer duty.

But there is a fundamental question we rarely ask:

If we already know a product is harmful,

why are we designing it in the first place?

Why design a product that:

-

has low utility,

-

cannot be recycled,

-

harms health or ecosystems,

…and then place the burden on consumers to “choose the lesser evil”?

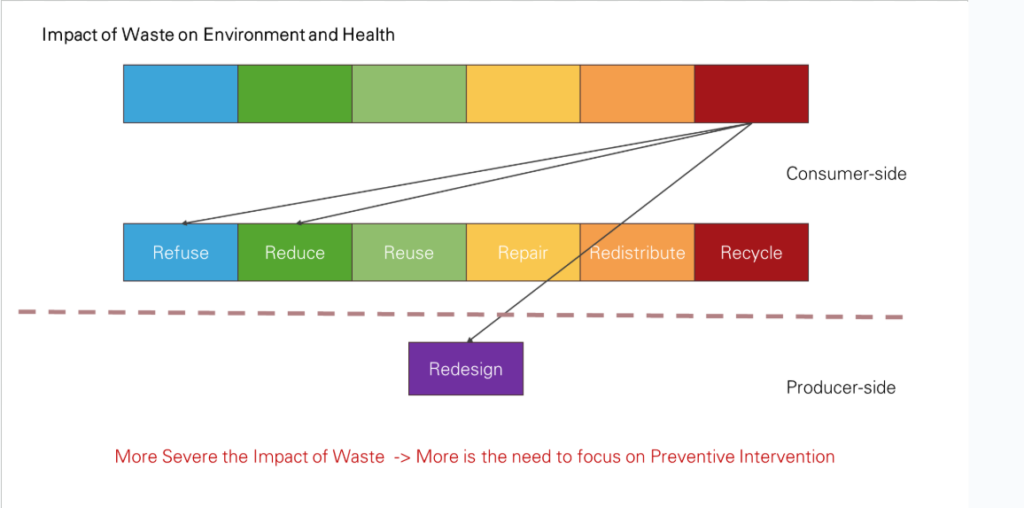

The R Framework: Correct Logic, Wrong Target

The hierarchy of actions is scientifically sound:

Refuse → Reduce → Reuse → Repair → Redistribute → Recycle

But in practice, this framework is applied almost entirely on the consumer side.

Consumers are told to:

-

refuse plastic straws

-

reduce sachet usage

-

recycle multilayer packaging

Meanwhile, design decisions remain untouched.

This creates a paradox:

The most damaging products are allowed to exist,

as long as consumers are instructed to manage their guilt.

The Missing Layer: Impact Severity vs Intervention Point

The more severe the environmental and health impact of waste,

the greater the need for preventive intervention — not downstream management.

Yet what do we see in reality?

| Impact Severity | Typical Response |

|---|---|

| Low | Refuse / Reduce |

| Medium | Reuse / Repair |

| High | “Recycle responsibly” |

This is backwards.

High-impact products should never rely on recycling as a solution.

Recycling Is the Weakest Intervention — Not the Strongest

Recycling sits at the end of the R framework for a reason:

-

It is energy-intensive

-

It is economically fragile

-

It often leads to downcycling

-

Many products are technically recyclable but practically unrecyclable

Yet recycling is the only intervention consistently funded, advertised, and promoted.

Why?

Because recycling allows harmful product designs to continue without disruption.

The Uncomfortable Question: Why Design “Known Bad” Products?

Let’s be honest.

We already know that:

-

Multi-layer sachets cannot be recycled at scale

-

Plastic + food + heat causes health risks

-

Thin plastics fragment into microplastics

-

Single-use items guarantee waste

Yet these products are still:

-

approved,

-

subsidised,

-

marketed,

-

normalised.

And then consumers are told:

“Use less.”

“Dispose responsibly.”

“Choose better alternatives.”

This shifts responsibility away from design and onto behaviour.

Redesign: The Most Powerful R That Is Ignored

Why redesign matters most:

-

It prevents waste before it exists

-

It protects health silently

-

It eliminates the need for consumer vigilance

-

It scales automatically across millions of users

One redesign decision can remove:

-

millions of sachets,

-

tonnes of plastic,

-

decades of pollution.

No consumer campaign can match that impact.

Redesign Is Preventive Governance, Not Innovation

Redesign does not always mean inventing new materials.

Often, it simply means:

-

returning to durable formats,

-

eliminating unnecessary components,

-

choosing mono-materials,

-

removing low-utility features.

Steel tiffins, glass bottles, cloth napkins, bulk dispensers —

these are not futuristic solutions.

They are proven designs that were replaced by disposables.

Why the Burden Must Shift Upstream

Placing responsibility on consumers assumes:

-

equal access,

-

equal awareness,

-

equal choice.

None of this is true.

Design decisions, however:

-

shape defaults,

-

limit choices,

-

determine waste outcomes.

That is why waste is a policy and design issue, not a lifestyle failure.

A Reframed R Framework (Upstream First)

Here is how the hierarchy should actually function:

-

Redesign (Producer responsibility)

-

Refuse (Enabled by design)

-

Reduce (Enabled by systems)

-

Reuse & Repair (Supported by infrastructure)

-

Redistribute

-

Recycle (Last resort, not justification)

If redesign is done right,

most consumers never need to “refuse” consciously.

The Core Principle We Must Accept

We cannot keep designing harmful products

and then educating people to avoid them.

That is not sustainability.

That is abdication of responsibility.

Conclusion: Prevention Is Not a Consumer Choice — It Is a Design Duty

The R Framework was never meant to be a checklist for households alone.

It was meant to guide where intervention should occur.

And the evidence is clear:

-

The higher the harm,

-

the earlier the intervention must happen.

If a product is known to be harmful,

the ethical response is to redesign or eliminate it — not market it better.

The One-Line Takeaway

Severe waste impacts demand preventive design,

not better consumer behaviour.